Key Takeaways

- Efflorescence is a Symptom: The white powder shows moisture migration within the substrate, not a paint failure.

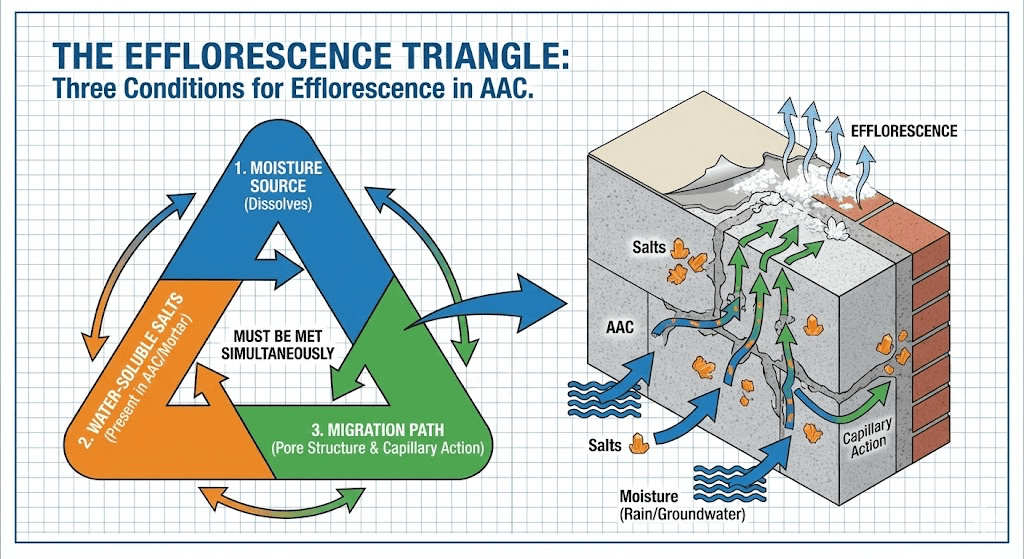

- The Efflorescence Triangle: Salts, moisture, and a path (pores) must all be present for it to occur.

- Diagnosis is First: You must stop the water source (if Secondary Efflorescence) before any cleaning starts.

- Alkali-Resistant Barrier: AAC’s high alkalinity (pH 12–13) requires a specialized Alkali-Resistant Primer.

- Coatings Must Be Breathable: The final paint must be vapor permeable to prevent hydrostatic pressure from building up.

Introduction

Efflorescence—the deposition of crystalline salts on the surface of masonry—is a prevalent issue in Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC) due to its unique porous structure. While often mistaken for a purely aesthetic issue, it indicates moisture migration that can compromise coating adhesion (delamination) and structural integrity if left unchecked. This technical write-up details the chemical mechanisms of salt migration and the standard operating procedure (SOP) for surface preparation prior to painting.

Efflorescence is not a reaction of the paint, but a symptom of the substrate. For it to occur, three specific conditions (The Efflorescence Triangle) must be met simultaneously:

- Water-Soluble Salts: Must be present in the AAC or mortar.

- Moisture Source: Water to dissolve the salts.

- Migration Path: A pore structure allowing capillary action to transport the solution to the surface.

What Causes the Efflorescence Triangle in AAC?

Efflorescence occurs when water-soluble salts, a moisture source, and a migration path (capillary action) are present simultaneously within the AAC or mortar matrix.

The three conditions that must be met are:

- Water-Soluble Salts: Present in AAC or mortar.

- Moisture Source: Water (Rain/Groundwater) that dissolves the salts.

- Migration Path: The pore structure of the AAC and capillary action.

What is the Chemical Mechanism of Salt Migration?

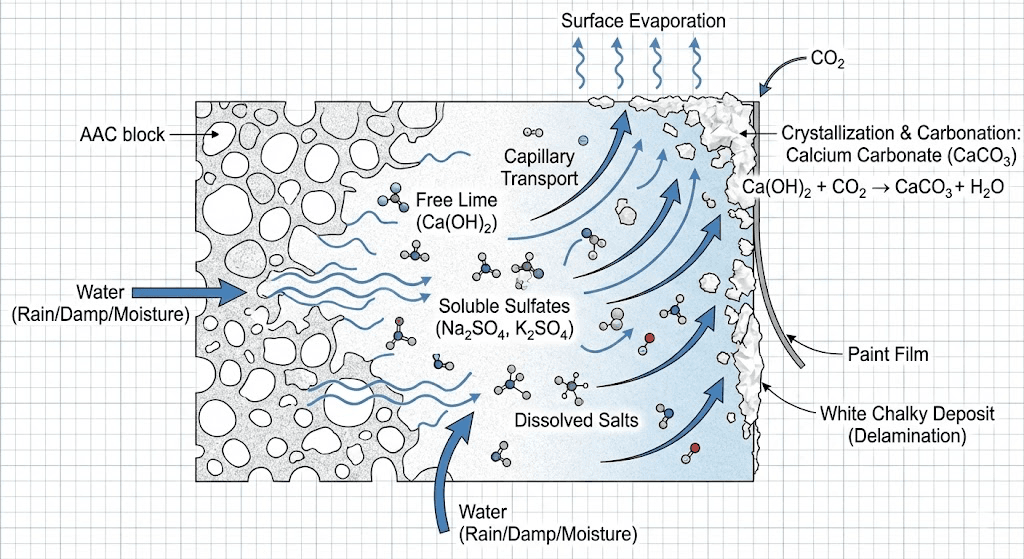

The migration process follows a thermodynamic pathway where water dissolves free Calcium Hydroxide, transports it via capillary suction to the surface, and reacts with atmospheric Carbon Dioxide to form Calcium Carbonate.

AAC blocks are composed of lime (CaO), cement, sand/fly ash, and an expansion agent (aluminum powder). Upon autoclaving, Calcium Silicate Hydrates (C-S-H) form the strength matrix. However, unreacted free lime and soluble alkalis remain.

The migration process follows this thermodynamic pathway:

- Dissolution: Water (from rain, rising damp, or construction moisture) permeates the AAC matrix, dissolving free Calcium Hydroxide Ca(OH)₂ and other soluble sulfates (Na₂SO₄, K₂SO₄).

- Capillary Transport: AAC contains a distinct macro-pore structure (aeration) connected by micro-capillaries. As surface water evaporates, it creates “suction,” drawing the salt-laden water from the interior to the surface.

- Crystallization & Carbonation: Once the water evaporates at the surface, the salts crystallize. The most common form on AAC is the reaction of leached Calcium Hydroxide with atmospheric Carbon Dioxide:

Ca(OH)₂ + CO₂ → CaCO₃ + H₂O

This results in Calcium Carbonate CaCO₃, a white, insoluble, chalky deposit that pushes paint films off the surface (delamination).

Why is AAC Specifically Vulnerable to Efflorescence?

AAC has high permeability to water vapor, meaning if walls are painted before internal moisture content stabilizes below 12-15%, hydrostatic pressure will force salts to the interface, causing blistering.

Unlike dense concrete, AAC’s high permeability means:

- Internal moisture must stabilize (typically <12-15%) before coating.

- If painted too early, the hydrostatic pressure of evaporating water forces salts to the interface between the block and the paint.

This pressure leads to blistering and loss of adhesion.

How Do You Remediate AAC Masonry Efflorescence?

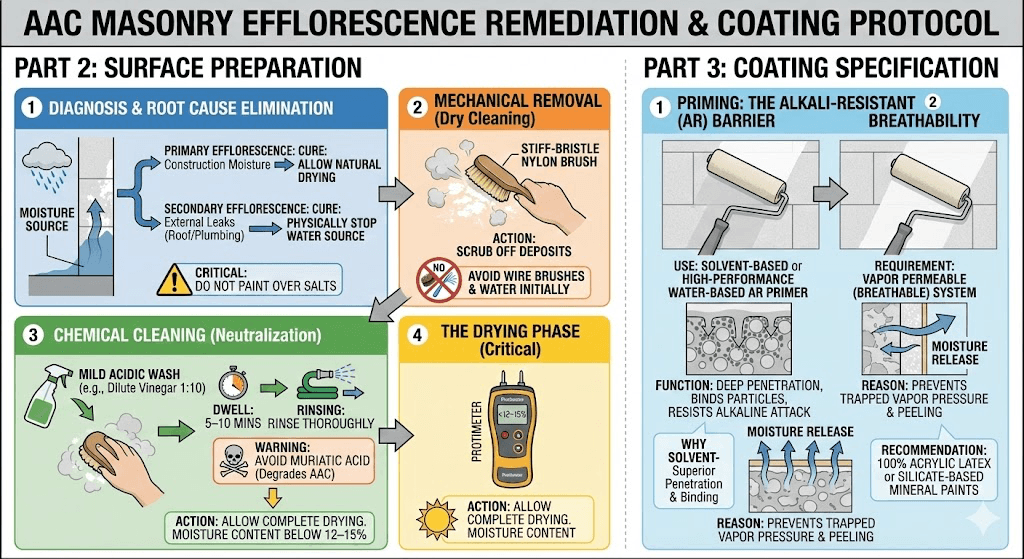

Remediation requires a four-step protocol: diagnosing the moisture source, mechanical dry removal of deposits, chemical neutralization with a mild acidic wash, and a critical drying phase to reach <12-15% moisture content.

Painting over efflorescence is a guaranteed failure mechanism. The salts act as a “bond breaker.” The following protocol is recommended for remediation before coating:

Step 1: Diagnosis and Root Cause Elimination

Before touching the wall, verify the source of moisture.

- Primary Efflorescence: Caused by initial construction moisture. Cure: Allow the wall to dry naturally.

- Secondary Efflorescence: Caused by external leaks (roofing, plumbing, rising damp). Cure: The water source must be physically stopped. Cleaning the salts without stopping the water is futile.

Step 2: Mechanical Removal (Dry Cleaning)

- Action: Use a stiff-bristle nylon brush or scouring pad to remove surface deposits.

- Avoid: Do not use wire brushes (iron particles can rust and stain the AAC).

- Note: Do not use water yet. Washing the wall initially will re-dissolve surface salts and push them back into the pores, only for them to reappear later.

Step 3: Chemical Cleaning (Neutralization)

If mechanical removal is insufficient, a mild acidic wash is required to neutralize the alkalinity and dissolve stubborn carbonate deposits.

- Solution: Use a specialized efflorescence remover or a dilute solution of acetic acid (white vinegar) mixed 1:10 with water.

- Warning: Avoid Muriatic (Hydrochloric) Acid on AAC if possible. It is too aggressive and can degrade the calcium silicate matrix of the porous block.

- Application: Apply the solution, scrub gently, and allow it to dwell for 5–10 minutes.

- Rinsing: Rinse thoroughly with clean water to remove acid residues.

Step 4: The Drying Phase (Critical)

- The wall must be allowed to dry completely after cleaning.

- Use a Protimeter (Moisture Meter). Ideally, moisture content should be below 12–15% before applying any primer.

What is the Recommended Coating Specification for AAC?

A durable AAC coating system requires a high-performance Alkali-Resistant (AR) primer to bind chalky particles and a vapor-permeable (breathable) topcoat to prevent trapped vapor pressure.

Standard wall sealers often fail on AAC because they cannot handle the high alkalinity (pH 12-13) and “chalkiness” of the surface.

1. Priming: The Alkali-Resistant (AR) Barrier

You must use a solvent-based or high-performance water-based Alkali-Resistant Primer/Sealer.

- Function: These primers penetrate deep into the chalky surface, bind loose particles, and resist chemical attack from alkaline salts.

- Why Solvent-based?: Solvent-based penetrating sealers generally offer superior penetration into the micro-pores of AAC and better binding of residual chalky deposits compared to standard water-based sealers.

2. Topcoat: Breathability

- Requirement: The final paint system must be vapor permeable (breathable).

- Reason: AAC naturally absorbs and releases moisture. If a non-breathable (elastomeric or high-gloss enamel) film is applied, trapped vapor will build pressure behind the film, leading to efflorescence and peeling.

- Recommendation: Use high-quality 100% acrylic latex paints or silicate-based mineral paints.

Conclusion

Managing efflorescence in AAC masonry is not merely about surface cleaning; it requires a technical understanding of the “Efflorescence Triangle” and the chemical carbonation process. By ensuring the root cause of moisture is eliminated, following the dry-cleaning SOP, and specifying a breathable, alkali-resistant coating system, the structural and aesthetic integrity of the AAC masonry can be preserved. Always ensure moisture levels are verified with a Protimeter before proceeding with any final coating application.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between primary and secondary efflorescence?

Primary Efflorescence is caused by water that was trapped inside the masonry during the initial construction process (curing, mixing, rain) and is now drying out. Secondary Efflorescence is caused by an active external moisture source, such as a damaged pipe, a roof leak, or rising damp from the ground.

What is the safe moisture content level for AAC walls before priming?

The AAC wall must have a moisture content ideally below 12%–15% before you apply any primer or coating. It is mandatory to use a specialized moisture meter (like a Protimeter) to verify this reading. Applying paint above this threshold will trap moisture and cause blistering.

Can I use normal paint or sealer on AAC masonry?

No, standard paint or sealers are highly likely to fail on AAC. You must use a specialized Alkali-Resistant Primer to resist the block’s high alkalinity (pH 12–13). The final topcoat must also be vapor permeable (breathable) to allow the wall to naturally release moisture.

Why should I avoid washing the walls with water before dry cleaning?

Washing the wall with water first will re-dissolve the salts on the surface and push them back into the porous AAC block’s capillaries. The salts will then be drawn back to the surface as the water evaporates, causing the efflorescence to reappear. Always use a stiff nylon brush for mechanical (dry) removal first.

What is the chemical risk of using Muriatic (Hydrochloric) Acid on AAC?

Muriatic Acid is too aggressive and should be avoided on AAC masonry. It can severely degrade the calcium silicate matrix, which is the core strength component of the porous block. This compromises the entire substrate and can cause irreversible damage.